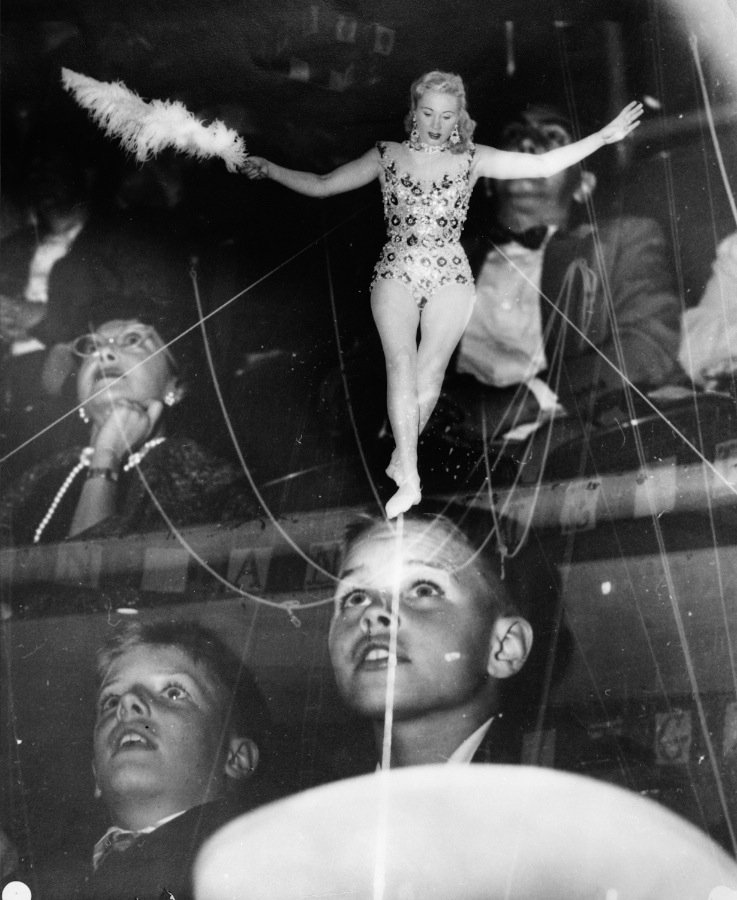

Running Away With the Circus

by Deborah J. Wolfinsohn

Running away with the circus.

Five little words that conjure up a dark, dusty dream from another time, a charmingly antique concept left to storybooks and Tom Waits songs.

But here at the Carson & Barnes Circus, it's still a reality, because the circus still depends on people showing up and joining on the spot.

So if you're willing to work hard for your room (trailer) board (coffee and rolls) and paycheck (100 bucks a week), you, too, can run away with the circus for real.

Like these guys, a knot of burly fellows in jeans and cowboy hats, all of them gathered in a vacant lot behind Lakeline Mall with their hands in their pockets, shivering in the pre-dawn air and speaking quietly to each other in Spanish until it's time to work. Today, this means transforming a pile of striped canvas into a giant, high-ceilinged room — the Big Top. They're assisted, with little fanfare, by an elephant named Susie.

As roustabouts — rousts, they're called — they avoid heading back to their hot, tiny trailers at any cost, preferring, instead, to roam the grounds looking for "cherry pies," all the odd jobs that pop up on a daily basis, from pony walking to ticket-taking, from truck driving to pitchforking fresh hay.

Not everyone lives in a tiny trailer, though. This town on wheels follows a surprisingly strict, three-tier class system.

First, the royalty — the production people and the circus owners in their big, deluxe RVs. As if to emphasize the class divide, a showgirl, doubling as a maid before today's show, stands on the threshold of a massive, wood-paneled motor home, shaking out rugs before going back in to dust the big-screen TVs.

Second, just across the way, you'll find the performers' trailers, modest but cozy and clean.

Then you have our friends the roustabouts, who cram into their tiny cells, trailers with four bunks and one bathroom to share. The doors on these trailers have the resident's names scribbled on duct tape, as if to remind everyone how temporary the whole strange situation is.

***

Thirteen-year-old Lisa Frisco sees none of these things as strange or unusual or even different. No, to her, it's just life, the only one she's ever known, and as she steers her 10-speed up the banked edges of the concrete ditch that will be her backyard for the next 24 hours, she's completely at ease. A true circus kid, her dad's in charge of the elephants, her dogs have been trained to jump on ponies backs, and she carries herself with the supreme confidence of a girl who's been performing since age three. Nothing really scares her anymore, she explains. She retired last year but misses the spotlight, discovering that taking tickets, clad in a blue Carson & Barnes sweatsuit, doesn't quite match up to lights, costumes and reporters clamoring for an interview.

Peering out from beneath stick-straight bangs, cheeks pink and green eyes full of sparkle, she laughs as she imagines spending the rest of her life in the circus. "There's a lot of kids here. It's great. We all play hide-and-seek at night,'' she says.

Her life sounds like a kid’s fever dream — a carefree existence full of elephants and popcorn and cotton candy, of late nights running wild under the stars and no school, ever. A few hours later, she hops off her bike to meet a friend behind the big top with plans to head into the mall, to spy "normal life" through a keyhole.

***

If Lisa ever has any questions about what this thing called "normal life" might be, all she has to do is ask her neighbors — Santa and Mrs. C.

Once upon a time (three years ago) Mrs. Colleen Stewart and her silver-bearded husband Ron were the very picture of normality, ensconced in a five-bedroom house in Seattle where Santa worked at Boeing and the Mrs. was a pre-school teacher. Santa retired, and, surrounded by their kids and grandkids, they could have surrendered happily to their golden years.

Instead, they gave the house to their kids, packed up the dogs, and joined the circus.

It was Santa's idea. He had always been a fan of the circus, so much that he subscribed to "route cards," which are postcards that tell you where the circus is heading next. So when the Hugo, Okla.-based Carson & Barnes Circus headed their direction, they showed up with their mobile home and offered themselves up. They didn't have any circus-related skills outside of their warm personalities, but they said, "Sure, come on down, we'll find something for you to do,"' remembers Santa. "They were glad to get us.''

In sensible navy flats and a bright pink shorts set, matching pink earrings and (pink, natch) lipstick, Mrs. C's perky energy makes her appear as though she's bouncing across a suburban golf course instead of picking her way through a wind-whipped field next to the highway. She shares the homey trailer, decorated with religious plaques, with her husband and her two dogs, Tinkerbell and Dynamite.

After a year on the road doing mundane activities like selling tickets, they became the "24-Hour Team," leaving in the mornings after the circus was set up and driving ahead to the next town to lay out the lot, place orders for supplies and direct the trucks and trailers to the site. Then they sleep, a lone little motor home emblazoned with "Nomad,'' parked in a dark field far from home, blue light of the TV flickering against the windows.

Once the circus arrives, they're on their way again, which keeps them somewhat removed from the gossip and love triangles and camaraderie and break-ups and babies, the social stuff that is such a big part of The Life, which is fine with them, because when you put 220 people together in close quarters for months at a time, drama happens.

The best evidence of this lies in this fact: most of the couples here met at the circus.

Like Cindy, the horseback rider, who married Roberto, the trapeze artist. Or John, the ringmaster, who married Reyna, the showgirl. And then there's Traci, the business manager, who married Julio, the trapeze artist.

The products of these unions, the circus babies, run in packs like little tigers. That is, when they're not helping out.

Twenty-five-year-old Noe Morales eats his lunch nearby, taking big forkfuls of food from a stainless steel tray: shredded pink meat, white bread and pinto beans, as his wife, Joyce, a black-haired beauty with a dancer's posture, helps interpret. Next to her, their three-year-old daughter Nicole sits and eats, her long black braids fastened atop her head like a crown.

They met at church in Reno, Nev., where he worked at a circus, she at a casino. This year, she decided to join him on the road. She's even in the act, mostly smiling and posing, glitter-encrusted arms outstretched toward her husband.

Noe, a third-generation trapeze artist, plans to retire in a few years. "You don't know what it is to wake up every day, every single morning at five," he says in Spanish. He dreams, oddly enough, of working as a truck driver. Joyce adds, hopefully: "Maybe truck driving is the closest thing where we could settle down.''

Is their daughter going to become a trapeze artist like her father? "Yes," says Noe, firmly, in English, looking across the table at the fourth generation as she plays with her food.

***

There’s a million reasons for joining. Heartbreak. Rent's due. Job sucks. The way your heart caught on something when you walked into that empty lot and saw the colored blinking lights and the striped tent, smelled the clean hay and the cotton candy, saw the man with the mustache leading an elephant around the ring.

Or maybe it was just that crazy organ music.

—April 3, 1997

Post a comment